|

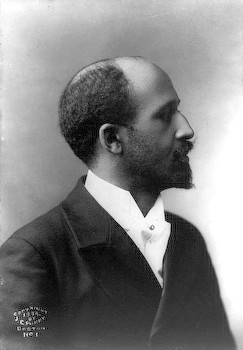

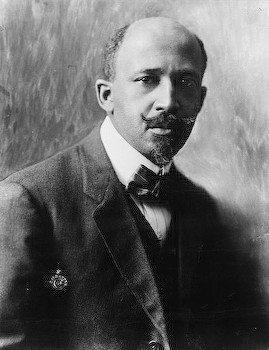

William

Edward Burghardt Du Bois, February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an

intellectual leader in the United States as sociologist, historian, civil

rights activist, Pan-Africanist, author, and editor. Biographer David

Levering Lewis wrote “In the course of his long, turbulent career, W. E. B.

Du Bois attempted virtually every possible solution to the problem of

twentieth-century racism—scholarship, propaganda, integration, national

self-determination, human rights, cultural and economic separatism,

politics, international communism, expatriation, third world solidarity.” William

Edward Burghardt Du Bois, February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an

intellectual leader in the United States as sociologist, historian, civil

rights activist, Pan-Africanist, author, and editor. Biographer David

Levering Lewis wrote “In the course of his long, turbulent career, W. E. B.

Du Bois attempted virtually every possible solution to the problem of

twentieth-century racism—scholarship, propaganda, integration, national

self-determination, human rights, cultural and economic separatism,

politics, international communism, expatriation, third world solidarity.”

Born in Massachusetts, Du Bois graduated from Harvard, where he earned his

Ph.D in History, the first African-American to earn a doctorate at Harvard.

Later he became a professor of history and economics at Atlanta University.

As head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)

in 1910, he was founder and editor of the NAACP's journal The Crisis. Du

Bois rose to national attention in his opposition of Booker T. Washington's

alleged ideas of accommodation with Jim Crow separation between whites and

blacks and disfranchisement of blacks in the South, campaigning instead for

increased political representation for blacks in order to guarantee civil

rights, and the formation of a Black elite who would work for the progress

of the African-American race.

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was

born on February 23, 1868, in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, to Alfred Du

Bois and Mary Silvina Burghardt Du Bois. He grew up in Great Barrington, a

predominately Anglo-American town. Mary Silvina Burghardt's family was part

of the very small free black population of Great Barrington, having long

owned land in the state. Their family descended from Dutch and African

ancestors. Tom Burghardt, a slave (born in West Africa around 1730) earned

his freedom by service (1780) during the American Revolution as a private

soldier in Captain John Spoor's company. According to Du Bois, several of

his maternal ancestors were notably involved in regional history.

Alfred Du Bois, from Haiti, was of French Huguenot and African descent. His

grandfather was Dr. James Du Bois of Poughkeepsie, New York. Dr. Du Bois's

family was rewarded extensive lands in the Bahamas for its support of King

George III during the American Revolution. On Long Cay, Bahamas, James Du

Bois fathered several children with slave mistresses. When he returned to

New York in 1812, Du Bois brought with him John and Alexander, two of his

mixed-race sons, to be educated in Connecticut. After James Du Bois died,

his black sons were disowned by his family and forced to give up schooling

for work. Alexander became a merchant in New Haven and married Sarah Marsh

Lewis, with whom he had several children. In the 1830s Alexander went to

Haiti to try to salvage his inheritance. His son Alfred was born there in

about 1833. Alexander returned to New Haven without the boy and his mother.

Alfred Du Bois and Mary Silvina Burghardt married on February 5, 1867, in

Housatonic, Massachusetts. Alfred deserted Mary by the time their son

William was two. The boy was very close to his mother. When he was young,

Mary suffered a stroke which left her unable to work. The two of them moved

frequently, surviving on money from family members and Du Bois's

after-school jobs. Du Bois believed he could improve their lives through

education. Some of the neighborhood whites noticed him, and one rented Du

Bois and his mother a house in Great Barrington. During these years, Du Bois

attended the First Congregational Church of Great Barrington.Du Bois

performed chores and worked odd jobs. He did not feel separate because of

his skin color while he was in school. He has suggested that the only times

he felt out of place were when out-of-towners visited Great Barrington. One

such incident occurred when a white girl who was new in school refused to

take one of his "calling cards" during a game; the girl told him she would

not accept it because he was black. Du Bois then realized that there would

always be a barrier between some whites and non-whites.

Du Bois faced some challenges as the precocious, intellectual, mixed-race

son of an impoverished single mother. His intellectual gifts were recognized

by many of his teachers, who encouraged him to further his education with

classical courses while in high school. His scholastic success led him to

believe that he could use his knowledge to empower African Americans.

In 1888 Du Bois earned a degree from

Fisk University, a historically black college in Nashville, Tennessee.

During the following summer, he managed the Fisk Glee Club, which was

employed at a luxury summer resort on Lake Minnetonka in suburban

Minneapolis, Minnesota. The resort was a favorite of vacationing wealthy

American Southerners and European royalty. In addition to providing

entertainment, Du Bois and the other club members worked as waiters and

kitchen help at the hotel. In 1895, Du Bois became the first African

American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University. After teaching at

Wilberforce University in Ohio, he worked at the University of Pennsylvania.

He taught while undertaking field research for his study The Philadelphia

Negro. Next he moved to Georgia, where he established the Department of

Social Work at Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta University Whitney M.

Young school of Social Work). He also taught at The New School in Greenwich

Village, New York City. The young Du Bois was put off by the drinking, crude

behavior, and sexual promiscuity of the rich white guests at the hotel.

Du Bois entered Harvard College in the fall of 1888, having received a $300

scholarship. He earned a bachelor's degree cum laude from Harvard in 1890.

In 1892, he received a fellowship from the John F. Slater Fund for the

Education of Freedmen to attend the University of Berlin for graduate work.

While a student in Berlin, he traveled extensively throughout Europe. He

came of age intellectually in the German capital, while studying with some

of that nation's most prominent social scientists, including Gustav von

Schmoller, Adolph Wagner, and Heinrich von Treitschke.

Du Bois was the most

prominent intellectual leader and political activist on behalf of African

Americans in the first half of the twentieth century. A contemporary of

Booker T. Washington, he carried on a dialogue with the educator about

segregation, political disfranchisement, and ways to improve African

American life. He was labeled "The Father of Pan-Africanism." Along with

Washington, Du Bois helped organize the "Negro exhibition" at the 1900

Exposition Universelle in Paris. It included Frances Benjamin Johnston's

photos of Hampton Institute's black students. The Negro exhibition focused

on African Americans' positive contributions to American society. Du Bois was the most

prominent intellectual leader and political activist on behalf of African

Americans in the first half of the twentieth century. A contemporary of

Booker T. Washington, he carried on a dialogue with the educator about

segregation, political disfranchisement, and ways to improve African

American life. He was labeled "The Father of Pan-Africanism." Along with

Washington, Du Bois helped organize the "Negro exhibition" at the 1900

Exposition Universelle in Paris. It included Frances Benjamin Johnston's

photos of Hampton Institute's black students. The Negro exhibition focused

on African Americans' positive contributions to American society.

Du Bois is viewed by many as a modern day prophet. This is highlighted by

his "Credo", a prose-poem first published in The Independent in 1904. It was

reprinted in Darkwater in 1920. It was written in style similar to a

Christian creed and was his statement of faith and vision for change. Credo

was widely read and recited. In 1905, Du Bois, along with Minnesota attorney

Fredrick L. McGhee and others, helped found the Niagara Movement with

William Monroe Trotter. The Movement championed freedom of speech and

criticism, the recognition of the highest and best human training as the

monopoly of no caste or race, full male suffrage, a belief in the dignity of

labor, and a united effort to realize such ideals under sound leadership.

The alliance between Du Bois and Trotter was, however, short-lived, as they

had a dispute over whether or not white people should be included in the

organization and in the struggle for civil rights. Believing that they

should, in 1909 Du Bois with a group of like-minded supporters founded the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In 1910,

Du Bois left Atlanta University to work full-time as Publications Director

at the NAACP. He also wrote columns published weekly in many newspapers,

including the Hearst-owned San Francisco Chronicle as well as the African

American Chicago Defender, the Pittsburgh Courier and the New York Amsterdam

News. For 25 years, Du Bois worked as editor-in-chief of the NAACP

publication, The Crisis, then subtitled A Record of the Darker Races. He

commented freely and widely on current events and set the agenda for the

fledgling NAACP. The journal's circulation soared from 1,000 in 1910 to more

than 100,000 by 1920.

Du Bois published Harlem Renaissance writers Langston Hughes and Jean Toomer.

He encouraged black fiction, poetry and dramas. As a journal of black

thought, the Crisis was initially a monopoly, David Levering Lewis observed.

In 1913, Du Bois wrote The Star of Ethiopia, a historical pageant, to

promote African-American history and civil rights. Du Bois thought blacks

should seek higher education, preferably liberal arts. He also believed

blacks should challenge and question whites on all grounds. Booker T.

Washington believed assimilating and fitting into the "American" culture was

the best way for blacks to move up in society. While Washington stated that

he did not receive any racist insults until his later years, Du Bois said

blacks have a "Double-Conscious" mind in which they have to know when to act

"white" and when to act "black". Booker T. Washington believed that teaching

was a duty, but Du Bois believed it was a calling.

Du Bois became increasingly estranged from Walter Francis White, the

executive secretary of the NAACP. He began to question the organization's

opposition to all racial segregation. Du Bois thought that this policy

undermined those black institutions that did exist. He believed that such

institutions should be defended and improved rather than attacked as

inferior. Du Bois seated with college members of the Beta Chapter of Alpha

Phi Alpha at Howard University in 1932By the 1930s, the NAACP had become

more institutional and Du Bois increasingly radical, sometimes at odds with

leaders such as Walter White and Roy Wilkins. In 1934, Du Bois left the

magazine to return to teaching at Atlanta University, after writing two

essays published in the Crisis suggesting that black separatism could be a

useful economic strategy.

As a member of the Princeton chapter of the NAACP, Albert Einstein

corresponded with Du Bois, and in 1946 Einstein called racism "America's

worst disease". During the 1920s, Du Bois engaged in a bitter feud with

Marcus Garvey. They disagreed over whether African Americans could be

assimilated as equals into American society (the view held by Du Bois).

Their dispute descended to personal attacks, sometimes based on ancestry. Du

Bois wrote, "Garvey is, without doubt, the most dangerous enemy of the Negro

race in America and in the world. He is either a lunatic or a traitor."

Garvey described Du Bois as "purely and simply a white man's nigger" and "a

little Dutch, a little French, a little Negro ... a mulatto ... a

monstrosity." Du Bois became an early member of Alpha Phi Alpha, the first

intercollegiate Greek-letter fraternity established by African Americans,

and one that had a civil rights focus.

Du Bois was invited to Ghana in 1961 by

President Kwame Nkrumah to direct the Encyclopedia Africana, a government

production, and a long-held dream of his. When, in 1963, he was refused a

new U.S. passport, he and his wife, Shirley Graham Du Bois, became citizens

of Ghana. Contrary to some opinions (including David Levering Lewis's

Pulitzer Prize winning biography of Du Bois), he never renounced his US

citizenship, even when denied a passport to travel to Ghana. Du Bois' health

had declined in 1962, and on August 27, 1963, he died in Accra, Ghana at the

age of ninety-five, one day before Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I Have a

Dream" speech. At the March on Washington, Roy Wilkins informed the hundreds

of thousands of marchers and called for a moment of silence. Du Bois is

buried at the Du Bois Memorial Centre in Accra. |